Atari Eastern Front 1941: browser redux

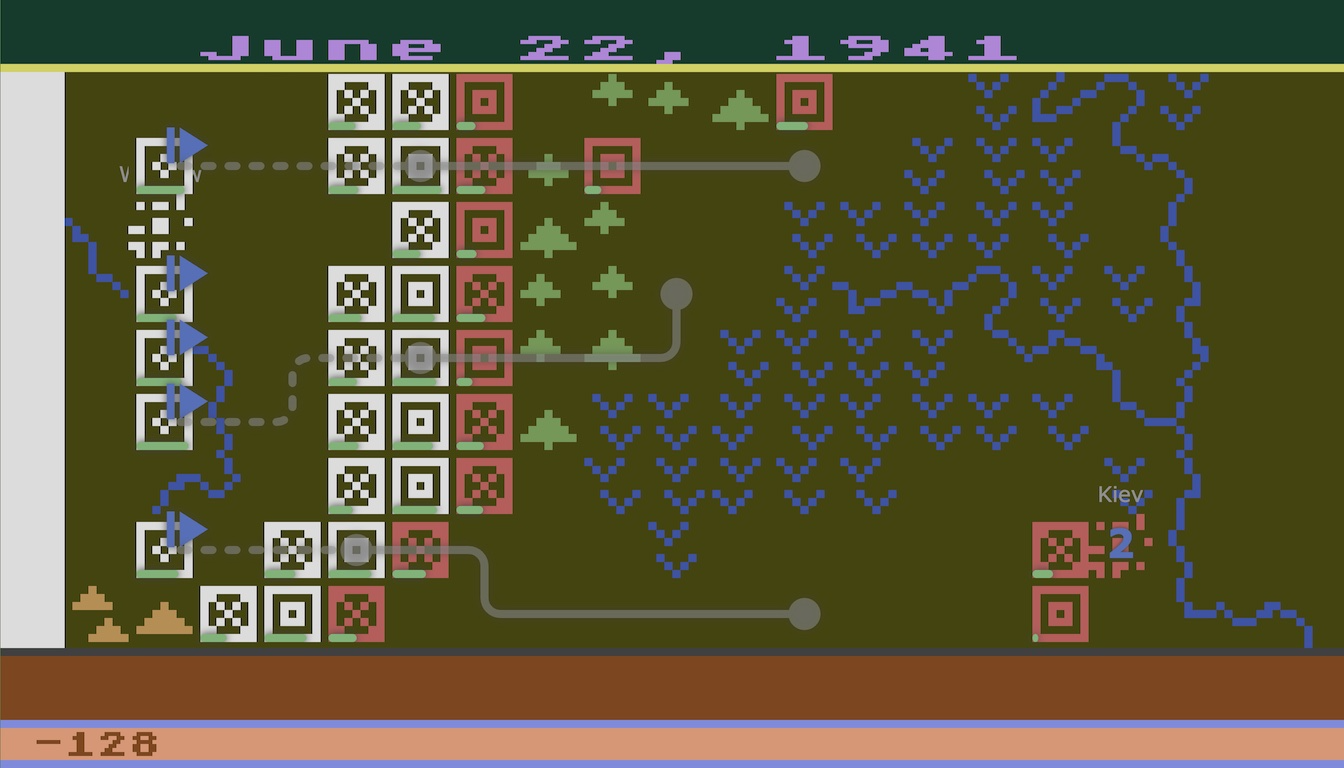

Check out my playable TypeScript port of Chris Crawford’s Eastern Front 1941. Can you capture Moscow? More importantly, how long can you hold it?

The project started as a pandemic diversion after chancing on an article about Atari’s 50th anniversary. I tumbled into a memory rabbit hole and discovered that Chris Crawford had published much of his early source code, including the 6502 assembler code for Eastern Front. The game had fascinated me as a kid: I remember hanging out after school with a friend who had an Atari 400 (or maybe 800?) to say nothing of an original Pong pub table :exploding_head:… We played games like Pitfall, Missile Command, Defender and a rogue-like adventure game whose name I forget. But Eastern Front was always my “Can we play…?” go-to. It was a compelling game in itself with a mysterious AI opponent, and was probably my first introduction to wargaming. So of course I couldn’t resist taking it apart! My goals were to understand how it worked, recreate the essence of the game in a streamlined form, and make it more accessible for others to explore and extend.

Along the way I had fun unravelling Crawford’s code, with happy memories of hacking 6502 assembly on an Apple //e back in the day. (Apparently I’m no better at keeping carry flag semantics straight.) I also learned a bunch of other things including TypeScript, Mithril and Jest. But more than anything I gained a whole new appreciation for Crawford’s technical tour-de-force: implementing an interactive wargame with a credible AI in only 12K bytes including all data and graphics. It shipped on a 16K cartridge with 4K to spare!

Eastern Front 1941 is a two player turn-based simultaneous movement simulation of the German invasion of Russia in 1941. It introduced many novel features including an AI opponent; multiple difficulty levels; terrain, weather, zone of control and supply effects; multiple unit types and movement modes including air support; fog of war; and an innovative combat system. The game was first released in 1981 on the Atari Program Exchange. It became a killer app for the Atari 8-bit computer family when it was widely released on cartridge in 1982, 41 years after the events of 1941 that it simulates. A further 41 years on, 2023 seems fitting for a redux.

The game’s subject matter offers disturbing echoes and distorted reflections of Putin’s recent unprovoked invasion of Ukraine which is being fought over significant areas of the same battlefield. So why revisit it? As Churchill (paraphrasing Santayana) said:

“Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.”

I believe the game still has a lot to teach us about early video game development, game design and AI play, and of course lessons from the history itself. Crawford’s own narrative history of the game’s development is well worth a read. As he says in his preface to the APX source notes:

“My hope is that people will study these materials to become better programmers […]”

And later in the cartrige insert:

“There was really no way to win this war. The [Expert] point system … reflects these brutal truths. … In other words, you’ll almost always lose. Does that seem unfair to you? Unjust? Stupid? Do you feel that nobody would ever want to play a game [they] cannot possibly win? If so, then you have learned the ultimate lesson of war on the Eastern Front.”

So in that spirit, my re-implementation tries to capture the essence of the game—reusing the same raw data, fonts, display style and color scheme—without slavishly recreating every pixel of the original. You can play the original ROMon an emulator like AtariMac but honestly the gameplay now feels painful. Crawford explicitly designed for play with only a joystick whereas I wanted a more efficient keyboard-driven experience. At the same time I wanted to make the game’s data and logic more approachable and easier to modify. For example data structures like the order-of-battle are still lists accessed by index, but are now wrapped as simple objects to attach meaningful names and methods to the content. Similarly most magic constants have become named enumerations. Heck, my laptop has sixteen million times the memory of an Atari 400 and perhaps ten thousand times the CPU power so we can afford to be a little more verbose…

I also aimed to keep the game engine completely separate from the display layer so that it can run “headless”. This is great for unit testing but also makes it easy to experiment with AI development and meta-learning of new strategies. The human player is also parameterized so AI vs AI play or playing as the Russians is possible, although the current AI does not play the Germans well. One of my hopes is that someone will come with better computer players for the game. Perhaps a future project…

Enjoy!